This is not only one of the most famous incidents in Cubs history, it's one of the most famous in baseball history. What really happened, though?

You all likely know the basics of the story of Game 1 of the 1932 World Series, where Babe Ruth allegedly "called his shot" off Cubs pitcher Charlie Root.

But did he really? The story has taken on the air of myth or legend over the decades.

Writers of the day, chronicling Game 1 for the Tribune, both concurred that Ruth was simply holding up two fingers, indicating that Root had two strikes on him. Ruth had hit a three-run homer in the first inning off Root, but the Cubs had come back to tie the game, and entering the fifth, it was 4-4. Ruth came up with one out and nobody on base. Edward Burns:

The Cub bench jockeys came out of the dugout to shout at Ruth. And Ruth shouted right back. Root got a strike past Babe, and did those Cub bench jockeys holler and hiss! After a couple of wide ones, Root whizzed another strike past the great man. More hollering and hissing and no small amount of personal abuse. Ruth held up two fingers, indicating the two strikes in umpire fashion. Then he made a remark about spotting the Cubs those two strikes. Well, it seems that Charley Root threw another good one. Mr. Ruth smacked the ball right on the nose and it traveled ever so fast. You know that big flag pole just to the right of the scoreboard beyond center field? Well that's 436 feet from home plate. Ruth's drive went past that flag pole and hit the box office on the corner of Waveland and Sheffield avenues. Ruth resumed his oratory the minute he threw down his bat. He bellowed every foot of the way around the bases, accompanying derisive roarings with wild and eloquent gesticulations.

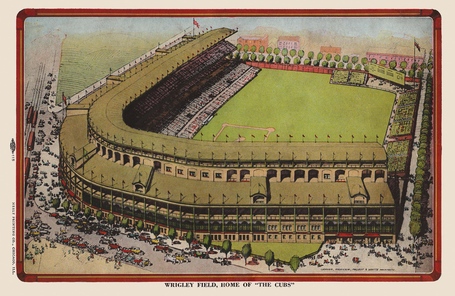

The "bench jockeying" of the day wouldn't be tolerated today, but it was common in that era, players yelling back and forth. Can you imagine a modern home run hitter doing what Ruth did in that report? Also, keep in mind that what Burns described was under the old configuration of Wrigley, before the current bleacher structure, when there was a scoreboard at field level near center field. The flight of that home run today would have taken it, likely, into the center-field bleachers, just below the current scoreboard location.

The Tribune's Irving Vaughn quoted Root and manager Charlie Grimm in his article:

"If I had to do it again, I'd pitch the same way," was the comment of Charley Root, who was in the midst of the batting carnage. "You can't guess 'em. You'll fool 'em on one and the next thing you know they've hit the ball over the fence," was declared by Grimm. "It was a change of pace ball, low outside," said Root. "If it had been a fast ball I wouldn't have been surprised. But he picked out a low curve and sent it on a line to center. That convinced me of the tremendous power he has in his swings."

No mention of called shots. Not one. Just a description of Ruth holding up two fingers indicating two strikes, and Root (note: his name was often spelled "Charley" during his playing days; today, we usually write "Charlie") admitting that Ruth just got all of one of his better pitches.

Several years ago, a home movie taken of this event was found. Here it is; you can judge for yourself.

Looks to me as if the contemporary descriptions were exactly right. Ruth points at the Cubs dugout, as described by Burns, and might have lifted two fingers before he hits the blast past the scoreboard. Called shot? Only embellished by writers over the years. It didn't really happen that way.

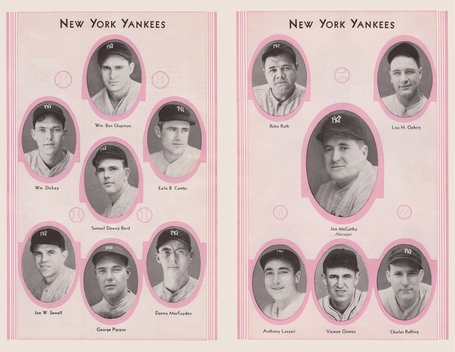

Ruth's home run was followed immediately by one from Lou Gehrig, and the Yankees wound up winning the game 7-5 and won Game 4 the next day, sweeping the series.

One more note on Game 3, from Arch Ward in the Tribune:

Hundreds of fans who arrived at Wrigley field after 1:15 o'clock yesterday were unable to get to their seats until after Babe Ruth had knocked his first home run. Consequently they missed one of the big thrills of the game. Inadequate entrance facilities forced many to stand in line for 20 minutes. This congestion was greatest at gates 1, 2 and 3. Four turnstiles were in operation at the Sheffield-Addison entrance and 11 at the main entrance. Several patrons protested that all the gates were not open, but this was denied by President William Veeck of the Cubs. "We had every turnstile in use," Mr. Veeck explained. "It is impossible to eliminate congestion when thousands attempt to enter at game time. There is no way we can provide more entrances."

I'm not sure where gates 1, 2 and 3 were in 1932; gates at Wrigley now have letters, rather than numbers. 1932 World Series games at Wrigley began at 1:30 (instead of the common regular-season time of 3 p.m.) to avoid darkness. But you can see that the nearly 20-year-old ballpark needed upgrading, even then.

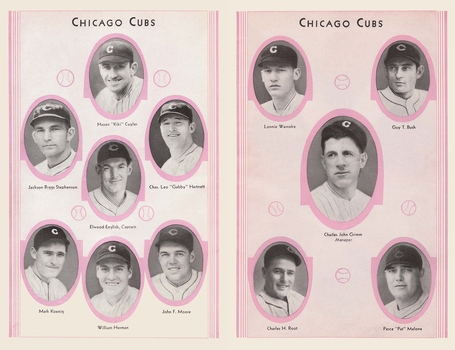

Here's the front and back cover and all the inside pages of the 1932 World Series program from Wrigley. You'll note on the scorecard pages that this is, in fact, a program sold on October 1, 1932 -- whoever bought it wrote in the pitchers from the game (Root, Malone and May for the Cubs; Pipgras and Pennock for the Yankees), but didn't keep score. Too bad; that would have been an awesome souvenir of that memorable day.